De-privatisation of urban planning

Whenever I am having dinner or a drink with (real) urban planners, I always ask them whether they ever make zoning plans. They are always furiously indignant and I don't get it, because they are designers and they don't make zoning plans. Which is strange because, potentially, a zoning plan could just create a new "Plan Zuid". Only that never happens. Indeed, it is generally poorly drafted, hopelessly outdated, unimaginative, legal rubbish.

The culprits for the fact that we have any zoning plans at all should probably be sought among the drafters of "La Charte d'Athènes"

During the 4th CIAM Congress in 1933, under the chairmanship of van Eesteren, a final declaration was drawn up in Athens, which was not published in occupied Paris until ten years later, edited by Le Corbusier. This charter advocated, among other things, the separation of living, working, traffic and recreation. And yes, why not, making sure you don't live next to a blast furnace and don't have a tannery in your backyard doesn't seem an unkind idea. Also, as it turned out, it is probably wise not to locate a fireworks storage site in the middle of a residential area as well as to make sure that a Boeing does not fly rakishly over your chimney every ten minutes.

So, the fact that on 1 August 1965, the WRO included the possibility of including "regulations on the use of land" did not seem such a stupid idea. It was also decided then that such a zoning plan had to be renewed every 10 years. Which, incidentally, never happens. But in the meantime, we are just fine with it. More than three quarters of our assignments are in one way or another a deviation from the prevailing zoning plan an Article 19. This makes sense because often these things were drawn up 20 to 30 years ago. So it is not surprising that we have started to use the land differently in the meantime. Zoning plans also make a lot of sensible things impossible. For instance, we once tried to make a nursery at the entrance to a "brain park". Seemed like a good plan, from the traffic jam at the entrance to the business park, you put your children out of the car on the kiss and ride lane. And while we're at it, shall we add a primary school and a supermarket? Of course we couldn't because the zoning was "high-end office functions" and not "special purposes" like education and retail. Or what about someone who, in his shed in the backyard, wrote software on a commercial basis and at some point soldered a circuit board and slid it into a computer. From that moment on, the solderer had become "light industry" and that was absolutely unacceptable in the Vinex district, especially if he also took on an employee. Imagine that one coming by car.

To make matters worse, municipalities no longer make their own zoning plans. There are hardly any urban planners employed by municipalities anymore and if there are any they are far too busy directing external agencies, professors Joost Schrijnen and Henco Bekkering explain in Binnenlandsbestuur (magazine for senior civil servants) of 25 July this year. According to the professors, urban planning has hit rock bottom. They are right about that, because how does something like this happen?

There is a meadow, a vacant factory site or an old sports field that needs to be used.

In general, many a project developer or construction company has long ago smelt that something could probably be done with it, so it is probably already owned by the market or there are countless third-party claims on it. Then an agency (Kuiper compagnons, Bügel Hajema, Wissing, RBOI/Buro Vijn to name a few) is hired, usually by the project developer itself, to make an image quality plan, structure vision or the like. This is a woolly piece with fine atmospheric images about the history of that site and about how harmoniously and beautifully the new development will fit into the existing landscape and fabric. This is piloted through the city council by the alderman, who is not an urban planner either, who of course is not opposed to so much beauty and especially so much greenery, where parking is always already completely solved and hidden behind greenery or underground.

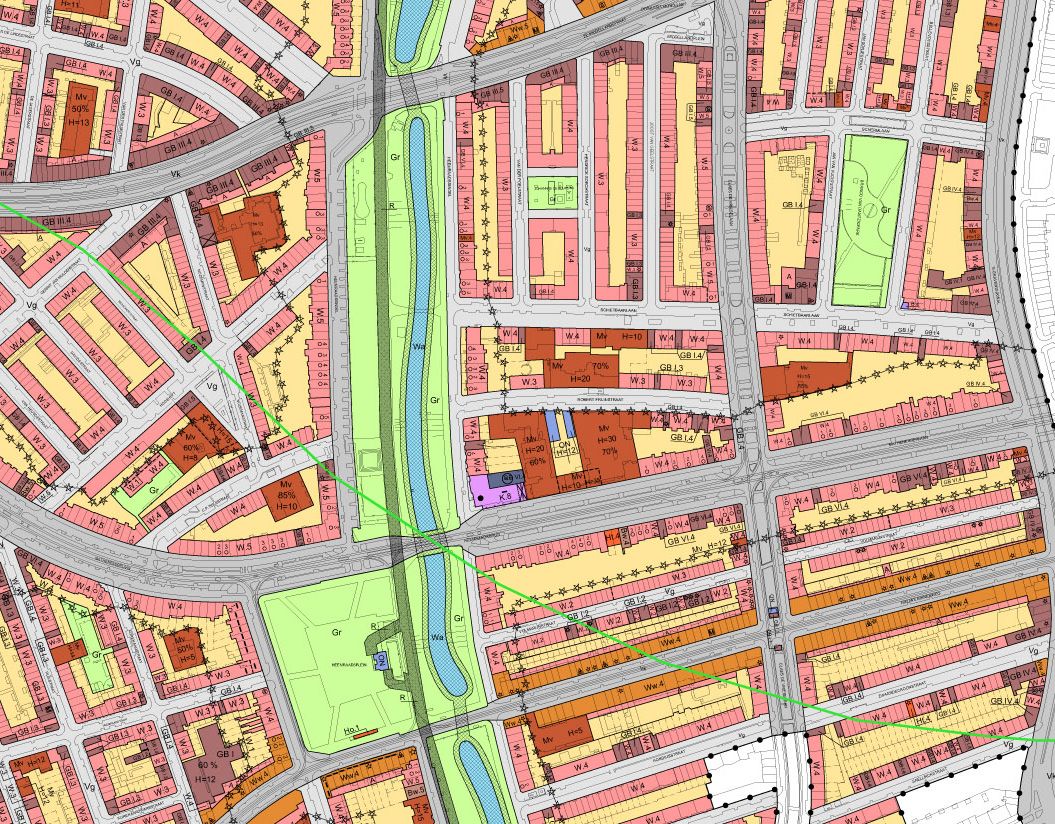

Next, a rock-hard zoning plan is drawn up, a thick legal document with a technical drawing where something is said in hard colours about numbers of houses, building areas, annexes, roof slopes, ridge and gutter heights and at best something about profiles. Incidentally, usually without any spatial concept behind it, other than: how much will fit? Should the municipal council or the ordinary citizen have anything to sputter about, it is subtly pointed out that this really is an elaboration of the image quality plan already approved by the council and that nothing else is possible. Certainly not because the plan now includes the sewer system, access for ambulances and fire brigade, lampposts, waste containers, heat pumps, number of playgrounds and the dog walking area. In short zoning plan adopted. And then the aesthetics committee is left to struggle to make something of it together with the architects. Once it's there, nobody is happy.

How to change this?

Municipalities have to start making their own urban development plans again. Make sure you have a fantastically paid, well-equipped urban planning department in-house. A combination of old hands who know the tricks and young ambitious designers supported by lawyers who understand. Then that service should get ahead of the market and thus serve the spatial interest. It is not at all difficult to see where something is going to happen in 10 or 20 years' time. Map those places and make sure you already have a plan for them. If someone comes forward to build something, you can give them the preconditions. An additional advantage is that politicians can also use it for architectural policy.

And put the urban designer in charge of such a team and not some random process controller from the chemical industry. It is an open door but still not for many a manager, a good plan is not an addition of all optimum solutions of all sub-problems, but a choice to make certain things subordinate so that the whole becomes better.

In addition, we should consider whether we should not just abolish the zoning plan. As far as environmental aspects are concerned, environmental laws are already often infinitely stricter than zoning plans. (You are no longer allowed to live next to a farmer with cows or next to Schiphol Airport at all, even though zoning plans still allow it) So we no longer need it for that. Urban planning specific and programmatically indeterminate. The only question is where we will then lay down the urban designs. Perhaps that belongs more to the design discipline rather than the legal programmatic one, in other words, in the building standards memorandum.

Jasper de Haan

October 2008